Donald Martiny: An Interview with Lynda Benglis

March 1, 2018

Artists on Art Magazine | March/April Issue

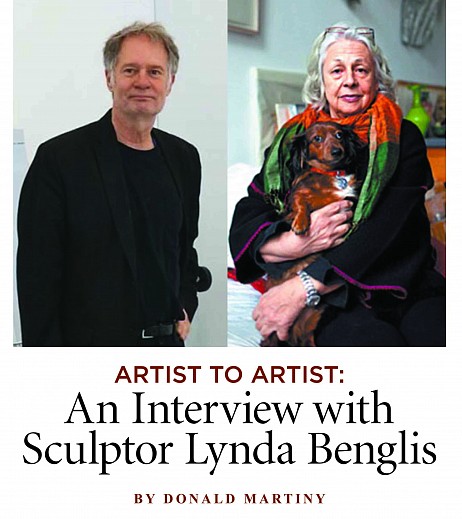

ARTIST TO ARTIST: An Interview with Sculptor Lynda Benglis

BY DONALD MARTINY

I was delighted to talk with artist Lynda Benglis. Since the 1960s, Lynda Benglis has been celebrated for the extraordinary artwork she forms by pouring, throwing or molding in clay, wax, latex, polyurethane, bronze, or paper.

Lynda was born in Lake Charles, Louisiana, and she currently lives and works between New York, Santa Fe, Greece, and India.

DONALD MARTINY: I have a vivid memory of the first time I saw your work. I had just arrived at the University in Kansas in 1971. On the first day I went straight to the the Union Art Gallery. It was there that I saw your work “Phantom,” now relocated to the Marianna Kistler Beach Museum of Art). It completely stopped me and challenged everything I thought art was supposed to be. I loved it and was so excited by it. In fact I believe it was instrumental in solidifying my decision to become and artist.

LYNDA BENGLIS: That’s a lovely statement.DM: How did it all start for you? Did you have art in your home? Were you encouraged to make art as a child?

LB: Well . . . I just always knew I wanted to be an artist. My mother was a painter. She got a degree from the University of Chicago and at the Art Institute of Chicago. She got an art degree, but she also got a teaching degree and taught in a one room schoolhouse in north Mississippi, in Faulkner country — near where Faulkner was born. Going to and from Mississippi from Louisiana was very exciting for me. It was a wonderful experience to travel by car over the Lake Pontchar-train bridge. When I was 11 years old I was asked by my grandmother to accompany her to Greece. She was from Greece, was married there and then came over. Going to Greece changed my life and my vision. The rocks and the water. I somehow felt connected to something I’d never seen before. Louisiana too has lots of water; swamps, rivers, lakes and bayous. So, I think the ideas came from nature. They came from the oil from my motorboat, that I had as a member of the country club. That kind of colorful thing that happens when oil spills on the water from the boats, what happens to materials when they got liquefied. So, that’s how I got ideas about marble-ization and waxing the linoleum that I pigmented and poured. My art developed out of nature, really.

DM: Then you went to school in New Orleans?

LB: Yes, I attended Sophie Newcomb in New Or-leans, now part of Tulane University. They had one of the best art schools, and were known for their pottery. It was expensive for my father be-cause he was just changing businesses and going out on his own. But I’d always been fascinated with New Orleans and Mardi Gras, masks and also Halloween … I love to dress up. It was very exciting. Noguchi [American-Japanese artist Isamu Noguchi] visited Newcomb when I was there. I was impressed with him, the fact that he was not only a sculptor, but he built bridges, and he was very handsome, and spoke very well. I was a painting major with a minor in clay. I love ceramics. I didn’t like the wheel, I liked to make forms, and I was doing pinch pots. Even today, I like those little pinch pots that I made, and they were rather classic.

DM: You still often work that way don’t you — create forms by squeezing clay?

LB: Yes, very much so. In fact, I installed a piece recently at the New Museum NYC. We’ve just completed it. It’s a beautiful piece.

DM: They are lucky to have it. In 1964, you moved to New York City, where you came in contact with a lot of the influential artists of that time: Andy Warhol, Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, Eva Hesse, and Barnett Newman.

LB: Yes, All of them, because I had met Gordon Hart, my first husband, who was teaching at the Brooklyn Museum Art School. I enrolled there because a friend who taught at Cooper Union suggested I go there. Gordon was a young Scottish painter that had worked with Bridget Riley. He was into some of the high key color, and was making these beautiful paintings. Gordon was much more ahead of me in that he actively started looking people up. He made friends with Tony Shafrazi straight away. Later we met Barnett Newman through Bridget Riley. When we met Barnett Newman, he was with Robert Murray and another artist . . . at a bar where they don’t allow women. What is the place around Cooper Union, where apparently they never allow women?

DM: Are you talking about McSorley’s?

LB: McSorley’s, yes, that’s what it is. So, I remember at that time, I just went in. DM: Ha! I can imagine the sound of necks cracking as men’s heads quickly turned to see a woman in there.

LB: And recently, maybe last year or a year or two ago the Village Voice said there was the first woman going into the bar. Which is bullshit. I was the first woman. So, I just want to dispel this idea that this woman thought she was the first woman. I know that I must have been … but I can’t believe there were no women in the bar mopping or doing anything else. Not having a drink of course.

DM: The art scene in New York was very exciting at that time.

LB: The pop artists were at their peak when I came to New York. So I was very interested in what came next. And as far as what came next after the pop scene, was the minimal scene. And I was interested in that because I thought in terms of logic. At Newcomb I enjoyed Greek philosophy and I had made very high grades in logic. My thinking was aligned with my Greek philosophy studies. So, my thinking about minimalism was, it was way out on a limb, and nothing could be done other than, you know, the trees . . . it was out there. So, I felt that I had to go back to a more physical approach to abstraction, and also limit my so-called deductions in order to arrive at something else. All my work is really based on a series of logical enclosed deductive things, and inductive, which is more scientific.

DM: Reacting to the minimalist works, you decided that you needed to go back to something more physical and more process-oriented. You felt that there was no way to go forward with it?

LB: Well, that was a way to go. I mean, I felt that I had an idea that didn’t really exist. Everything had some kind of enclosed system. Using that enclosed system that was there, way out on a limb, I felt that I could take a leap, so to speak.

DM: Once you had that notion, it must have been very liberating.

LB: So, that’s how I got ideas about marble-ization and waxing the linoleum that I pigmented and poured. I wanted to make a painting that’s a fallen painting. A painting that was relatively boundless in form. So, it was a sculpture as it began to look back at you, as they say. We have all these terms and rules, and what I took, basically, was Pollock’s term: “The painting looks back at you.” That was important to me, that something had a presence. That was something I learned when a professor talked about the physicality of say, Andrea Mantegna. His works have that physicality that we see. And that hit home, because I thought, well, you know, we have it in Pollock, we have it in Frankenthaler, and the whole Greenbergian thing. That’s when I made my first home pieces in the corner and around the corner and against the wall. My first show was at the Paula Cooper gallery. Paula had some good shows. In fact, it was her gallery where di Suvero, David Novros, and a whole host of other artists, maybe seven or eight artists began, the Park Place Gallery.*I had a class around the corner from the gallery and that’s how I discovered it. I met Paula the summer I first came to New York. There was a fellow named Walter that was a close friend of hers. He said he was showing with Paula in the brownstone where she lived. It turned out to be Walter De Maria and it was his first exhibition, along with another artist (Bob Thompson) whom she first showed.

DM: Then Paula Cooper opened her gallery in 1968 with an exhibition to benefit the student mobilization committee to end the Vietnam war. I believe it featured Sol LeWitt’s first wall drawing, and included works by Andre, Flavin, and Judd.

LB: Yes it was … it was mostly minimalist. Jack Smith, the performance artist, came in.

DM: Oh wow, Jack Smith. I’ve heard him called the founding father of American performance art. He made that film, Flaming Creatures sometime around 1961 or ’62.

LB: He looked like a creature that might have come from a snail, but he wasn’t slimy, he was just thin. But he was a wizened kind of guy. He started jumping around. He’d jump so high that he’d jump with his knees touching his chest and landed on my foam piece … on purpose! The piece kind of popped and crackled. It was a hard, rigid foam, one of the first I did. And so … he destroyed my piece.

On (Not) Being Judgmental in Work

DM: Lynda, sometimes your work is politically focused and then sometimes I see it as far more formal. Can you talk a little bit about that? Do you separate those two approaches?

LB: I think the hardest thing is to not be judgmental in work. And there, you know, the thinking is open. Other people like to categorize things, and certainly when you’re writing, you have to. But because there was the feminist movement, and also because there was another movement before that, and that was the racial one, you know, and my being from the South, I felt extremely sensitive with both issues. I didn’t feel that I could comment on the racial one, but I remember that growing up the class issue existed even in Louisiana as to the parish kids and the city kids. The parish kids sometimes had dairy farms, or lived outside of town and they didn’t wear shoes. I grew up in a public school, and thank god I did grow up in public school.

DM: In the 70s you made made some performance-based videos and you collaborated with artists — Robert Morris, on Mumble (1972) and Exchange (1973) and with Marilyn Lenkowsky on Female Sensibility (1973). Can you talk a little bit about how this came about?

LB: Well, I was very interested in going through the Anthology Film Archives. They did such good work, and nobody was going there. They even had a new building that was built. And before that they were showing films in the run-down area near Cooper.

DM: Yes, that beautiful building on 2nd Street with the big arched doorway.

LB: Then they bought a building finally, and I loaned them a fan, one of my fans that I did in India. Anyway, I made these fans out of wire, and actually folded them. I was doing that kind of thing in gold. Robert Morris at the time was doing some gold leafing of some pieces also. And his studio was near Grand Street, and I was near on Broom, just past the police station on Baxter Street. So it was easy for us to work together.

DM: How do you choose the titles for your work?

LB: Well, for their associations with the work. Not necessarily descriptive, always, but through associations.

DM: Can you talk a little bit about your last show at Cheim & Read? It was absolutely stunning. In fact, it was the most joyful and dynamic show I had seen in a very long time.

LB: That’s wonderful. I think, because of my … maybe it’s even fear of the flat plane, you know. It fell off, like Columbus or something. I had to prove that you could make sculpture and it could have many planes. So I began making my own paper. And I did it because of that fear of a piece of paper that every artist experiences. I began making my own paper and it mattered. It was matter. And I began to form it with some noble chicken wire.

DM: And there’s also associations with skin, would you say?

LB: Absolutely, absolutely. Every painting is a skin. And if its skin is not right, if it doesn’t feel right, it’s not a painting.

DM: What are you working on now?

LB: Paper sculpture, again. I’m trying to decide how I’m going to approach it. I’ve made some small forms here in Walla Walla. I’ve never made the paper here; I’ve made the large sculpture. And in my head, I’m working on a new metal piece, where I’m interested in the corner, and pulling it out from the corner. What the processes are, how to make a corner piece that’s tall. That’s my thinking lately. I don’t know what I’m going to do yet. I’m working it out in my head.

ABOUT DONALD MARTINY

Donald Martiny is an artist who currently lives and works in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Martiny was born in Schenectady, NY in 1953. He studied at the School of the Visual Arts, NY; The Art Students League, NY; New York University, NY; and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. Museum exhibitions include the FWMoA, IN; Courtauld Institute of Art, London; Alden B. Dow Museum of Art, MI; Falmouth Museum,Cornwall; and the Cameron Art Museum, NC. His work is currently on exhibit at the Historic City Hall, Lake Charles, LA.

In 2015 Martiny received a commission from the Durst Organization to create two monumental paintings that are permanently installed in the lobby of One World Trade Center in New York City.

Back to News